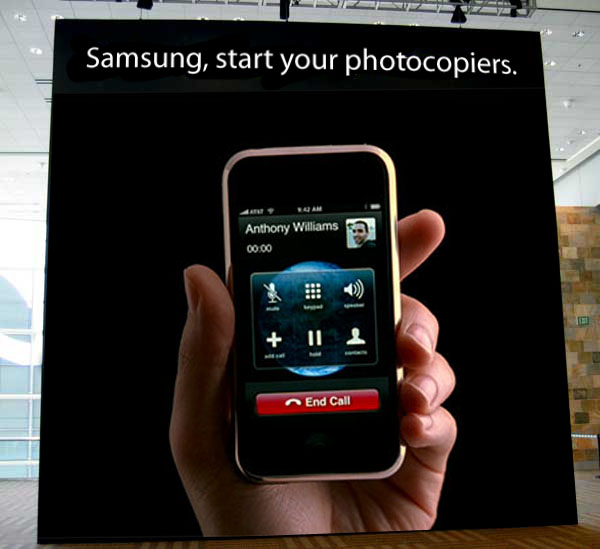

“They sat with the iPhone and went feature by feature, copying it to the smallest detail. In those critical three months, Samsung was able to copy and incorporate the core part of Apple’s four-year investment without taking any of the risks, because they were copying the world’s most successful product.â€

Thus spake Apple attorney Harold McElhinny to the jury during closing arguments of his company’s lawsuit against Samsung. I don’t think there is any disputing that McElhinny is right. In fact, what reads on the page as lawyer’s hyperbole is really a simple statement of fact: Samsung really did crawl through the iPhone feature by feature, stacking it against its original Galaxy S and concluding that in any instance in which the two devices differed, the latter should adopt the look and functionality of the former. There’s something almost admirable in the very brazenness of it.

What is not so admirable is the spectacle of the world’s most valuable company — not technology company or electronics company, mind, but most valuable, full stop — trying to stamp out one of its imitators not through the competitive marketplace but through the court system. To be blunt, Samsung indisputably copied Apple’s designs, but I don’t see anything in the law that ought to prevent them from doing it.

Certainly, if a company is building knockoff products designed to deceive buyers into thinking they’re purchasing a more popular competing device, that’s a different matter. Tricking people is wrong, in a different way that copying a competitor is wrong; counterfeiters look on those buying their products as marks, not customers. No one is alleging, at least not seriously, that Samsung was trying to trick people into buying its phones by making them think they were iPhones. There was no bogus Apple logo on the back. Anyone with the wattage to purchase and use a cellphone could distinguish between an iPhone and a Galaxy S.

I understand why Apple is undertaking this action. The $2.5 billion in damages the company is hoping to collect from Samsung is a nice chunk of change even by Apple’s standards. Beyond that, a decision in Apple’s favor would cast a collective pall over the mobile device landscape, and that I think is the real goal of this lawsuit. In fact, the actual decision handed down by the jury is probably irrelevant at this stage. Apple has shown the world what it is willing to do to protect its designs — and how much money it is willing to spend in the process. Lawsuits are expensive to prosecute and expensive to defend, no matter how much truth is on your side. No company is going to put itself through what Samsung is doing. Even now, you can bet there are pre-production devices in labs around the world being examined not by engineers but by lawyers, measuring bezels and scrutinizing icons to make sure nothing comes within suing distance of an Apple device. Devices will hit the marketplace designed, first and foremost, not to look like a competing Apple product.

You can see why this situation is a good one for Apple. But is it good for the rest of us? Do we really want a marketplace in which competition is so circumscribed? Does a company that’s already achieved such a sweeping competitive victory really need the machinery of the law to further grind down the other players?

You can see why this situation is a good one for Apple. But is it good for the rest of us? Do we really want a marketplace in which competition is so circumscribed? Does a company that’s already achieved such a sweeping competitive victory really need the machinery of the law to further grind down the other players?

I don’t want any of the above to imply that what Samsung did is commendable. As I said, part of me does admire the sheer ballsiness of it, but far more admirable would be to compete with the iPhone by surpassing it, not imitating it. But companies without originality eventually select themselves for extinction. It may take a while, but if Samsung is as bereft of originality as Apple claims, than Apple has nothing to worry about.

Years ago, Apple sued Microsoft for copying the Macintosh GUI in the first version of Windows. The suit failed because the court ruled that Windows wasn’t precise enough a copy: “Illicit copying,” a judge ruled, “could occur only if the works as a whole are virtually identical,” and similar as Windows was to the Mac, an identical copy it certainly was not. In subsequent years, after Steve Jobs returned and Apple once again assumed a leadership role within the computer industry, the company seemed more sanguine about its inventions being copied, teasing its rivals but otherwise accepting it as the price of innovation. But something happened within Steve Jobs after the iPhone came out. His rivals’ lack of originality was no longer a source of mordant ribbing; it prompted threats to go “thermonuclear” against what he considered “stolen” technology (i.e., Google’s Android operating system). It’s a view that has unfortunately survived him at Apple.

Apple may well win this case — certainly the evidence in their corner is much stronger than it was in the Macintosh/Windows lawsuit. But the mobile computing market will be a poorer place if they do.