“Is there anyone here who’s weak?!” jeers Roger Waters in the final act of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, and if the audience takes exception to his peculiar brand of misanthropic irony, their cheers give no indication. The product of Waters’ increasing alienation from—and contempt for—Pink Floyd’s enormous following, The Wall’s expansive brew of paranoia, oedipal terror, fascism and anti-war nostalgia is the symbolic capstone to the 70s prog-rock pyramid, and its accompanying live concerts remain a high-water mark of rock theater.

Though critics attacked its dominant metaphor as simplistic, even the die-hard Floyd-haters were bowled over by the presentation: a wall of hundreds of bricks was constructed steadily through the first half of the show, obscuring the entire stage (and the band) from the audience’s view and making the usual Floydian array of films, inflatable puppets, and pyrotechnics all the more vivid and powerful. At the show’s finale, when Waters bellowed “Tear down the wall!”, that’s exactly what happened: the wall tumbled down, the band took its bows, and the fans, it may be safely assumed, went out of their minds.

Of course, you’re not going to see any of that while listening to Is There Anybody Out There?, the long-awaited live recording of the Wall shows. No wall, no lasers, no animations, no nightmarish puppets of schoolteachers or castrating mothers–in fact, nothing of the grandiose invention that made the concerts so legendary. A video may yet be released (it’s rumored that the existing footage is of poor quality), but isn’t the point of a CD the music?

In this case the answer depends on your feelings, if any, for Pink Floyd in general and The Wall in particular. Critics usually slot Pink Floyd into the progressive rock family tree, home of great lumbering beasts like the Moody Blues, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, but Floyd’s rock n’ roll chops put them far beyond the reach of any of those bands; they could be pretentious, but they also could plug in and rock out — did Yes ever record anything approaching “Money” or “Have a Cigar”? Today’s Pink Floyd roadshow may be as bloated and boring as that of most other aging classic rock acts, but back in 1980 they still had enough muscle left to make an exciting noise; you don’t need to see the flying pig to want to reach for the volume knob. Even playing The Wall, a show with hundreds of cues that had to be met with split-second timing, they find room to stretch out and let the music take off: “Another Brick in the Wall Pt. 2” is embellished with a jivey organ solo, “Mother” is opened out with some soulful guitar work by David Gilmour and “Run Like Hell” is rougher, and better, than the more anesthetized studio version; I move that the version here replace the studio recording on classic rock radio playlists for at least the next five years.

So we admit the band can rock; but on the other hand, Pink Floyd created most of its best work under the riding crop of one of rock’s most notorious control freaks, and the fetish-like attention to detail evidenced here, with every sound bite, echo and bass fill from the album faithfully included, makes Is There Anybody Out There? more interesting as a document of Roger Waters’ theatrical élan—and his obsessiveness—than as a musical performance. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. You may hate Pink Floyd and you may really hate The Wall, but the album is still the most comprehensive statement ever made about the relationship between rock stars and their audience; it’s a flawed masterpiece, just like Sergeant Pepper (another album from a stadium rock act frustrated by an audience who cheered and screamed but no longer listened). With The Wall, Roger Waters attempted to overcome his alienation from Pink Floyd’s audience head-on, by flinging his frustrations back into their faces. The wall he built across the stage dramatized his feelings of imprisonment, but in a sense it imprisoned the audience too, forcing them on a frightening journey in which every atrocity the artist reveals, from losing a parent in war to being unfairly punished by a schoolteacher, is met with applause. (A sequence planned for the Wall film would have shown the audience being machine-gunned from the stage, and still cheering.) Waters wanted his audience to understand that such adulation, however well-meant, destroyed the artist’s soul, leaving him lonely, paranoid, and unable to regard the rest of humanity as deserving any more sympathy than a hive of ants. (Or, in more Watersian terms, worms.)

That The Wall was such a phenomenal success—it was #1 for months, selling something like 13 million copies—makes the story that much more remarkable. In a sense it’s a testament to failure; Waters must have known in his heart that the cheering Earls Court crowds weren’t really getting it. No wonder, introducing “Run Like Hell,” he becomes so wound up with mock rage it’s hard to know if he’s joking: “Put your hands together!” he bellows. “Have a good time! Enjoy yourselves!!“

Apple announced today a new service or product or category or something called Mastered for iTunes. You can see the thing for yourself in iTunes at this link courtesy of The Mac Observer; here is the description from Apple if you don’t want to bother reading it there:

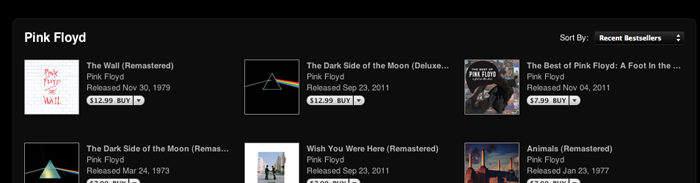

Apple announced today a new service or product or category or something called Mastered for iTunes. You can see the thing for yourself in iTunes at this link courtesy of The Mac Observer; here is the description from Apple if you don’t want to bother reading it there: Tastes come and go, but any format meant to appeal to serious audiophiles has to have the Floyd catalog. One day, music players may be able to stream music directly into our brains, leveraging the mind’s extraordinary sensory powers to make you feel as though you are within and surrounded by the music, inhabiting it in every fiber of your being, every nerve ending ablaze with it. And no one will buy it until you can play Dark Side of the Moon in it.

Tastes come and go, but any format meant to appeal to serious audiophiles has to have the Floyd catalog. One day, music players may be able to stream music directly into our brains, leveraging the mind’s extraordinary sensory powers to make you feel as though you are within and surrounded by the music, inhabiting it in every fiber of your being, every nerve ending ablaze with it. And no one will buy it until you can play Dark Side of the Moon in it.