Today Andrew Sullivan’s The Dish linked to a new tumblr called awesome people hanging out together. It lives up to its name. There are classic photos everyone knows, and quite a few I had no inkling of. It’s cool to see Jimi Hendrix greeting Janis Joplin (I can’t link to the photo itself) backstage — for all I know it’s the first time they ever met. Maybe the only time. Or Michael Jackson pretending to punch Mr. T — honestly, can you will yourself not to click that link?

One thing I was expecting to find, and did, was this:

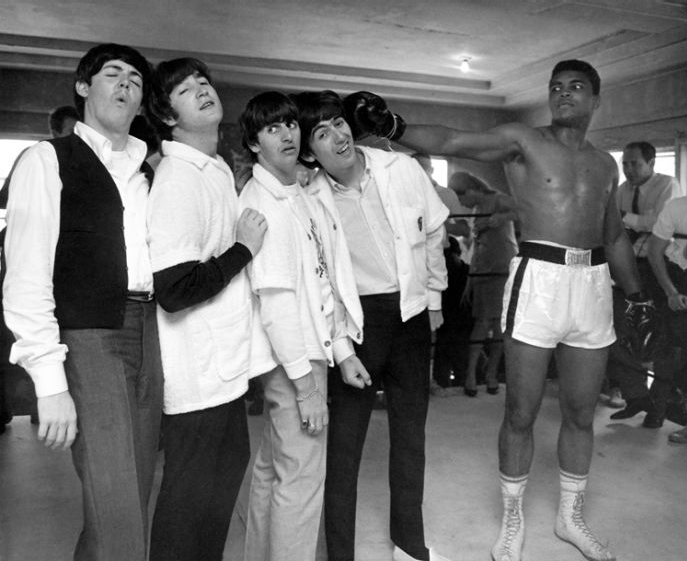

There are lots of pictures of the Beatles clowning around with Cassius Clay, as he was still known then, and this one and the variations of it are the best known. It might not occur to you on seeing it that the Beatles and Clay had no idea who each other were. The photo opp was arranged by their respective handlers, who had some inkling of what it might mean to bring these two phenomena together: the British invaders who were taking over American popular music, and the African-American dynamo who, not content to redefine the sport of boxing, went on to create the template for mass-media sports celebrity — he had already started doing it when this shot was taken.

There are lots of pictures of the Beatles clowning around with Cassius Clay, as he was still known then, and this one and the variations of it are the best known. It might not occur to you on seeing it that the Beatles and Clay had no idea who each other were. The photo opp was arranged by their respective handlers, who had some inkling of what it might mean to bring these two phenomena together: the British invaders who were taking over American popular music, and the African-American dynamo who, not content to redefine the sport of boxing, went on to create the template for mass-media sports celebrity — he had already started doing it when this shot was taken.

We see this photo now and marvel that it happened, that these five people ever occupied the same space together. It’s like an improbably real version of those cheesy prints that show Bogart, James Dean and Marilyn Monroe hanging out in the same pool hall. The Beatles and Muhammad Ali, to give him his proper name, are titans, figures who stand outside of popular history. It looked a little different to viewers back then. The Beatles were a teenybopper fad in February 1964, when they went to visit Clay as he trained for his first title fight. No one, perhaps not even the Beatles themselves, realized how pivotal their presence would be as the 60s took their strange, epochal course. And Clay was something of a nine-day-wonder himself, a braggart expected to have his clock cleaned by Sonny Liston. Probably a lot of people simply wanted it to happen, wanted to see the loudmouth get his comeuppance, just as a lot of people waited, and waited, for the Beatles to fall on their faces and prove how shallow and fleeting their presence in the culture really was.

But the Beatles went on to prove that rock music could expand beyond anyone’s preconceptions, taking politics, manners and culture along with it. And Ali proved not only that he was a great fighter — indeed, that he was as great as he said he was, which hardly seemed possible — but that a sports figure could be just as culturally radical, just as transformational, as any artist, politician, philosopher or pop musician.

It hadn’t happened yet. No one was seeing it coming. This is a photo of the moment before the plunge — before everything changed.