If you’re an Apple fan, an Apple user or just a technology enthusiast in general, there is only one story today: Steve Jobs is stepping down as CEO of Apple.

This is not to say he is leaving Apple. He is continuing on as Chairman of the Board, so it seems reasonable to assume he will still exert considerable direct influence on Apple’s products and overall direction. That face-saving news probably helped insulate Apple’s stock from the bad news. As of this writing, it has taken a five-percent hit, much less than the cataclysm many predicted would befall Apple should Jobs have died, quit or otherwise left the company abruptly.

Apart from sadness and a vague sense of unease or disquiet, I have these thoughts on hearing this news.

Whatever health issues Jobs has been dealing with, he has not been able to overcome them. Jobs must have reached a point where he and his doctors realized his recovery would make no more significant progress. It is possible (and I certainly hope) that Jobs has many years ahead of him in which to contribute to Apple and to enjoy life with his family and friends. However, it is just as possible — and knowing Jobs’ concern for his privacy, not at all unlikely — that there may be more bad news about Steve Jobs ahead, and that it will come sooner than anyone wants to accept. I take no pleasure in thinking that. But I do think it.

In a sense, we are about to see the ultimate test of Jobs as a businessman and leader. How well has he inculcated his values and expectations into Apple’s culture? How well, in other words, has he enabled it to continue as though he were still there? The answer to this question will not be apparent for some time; Jobs will, as noted, continue to be involved with Apple, and it will take months or even years for the efforts he has overseen to come to fruition. That will not, alas, stop the tech pundits from clucking over Apple’s “loss of vision” at the first post-Jobs bump in the road to come along. For example, if the iPhone 4’s “Antenna-gate” issue had happened at a post-Jobs Apple, no one would skip a beat before denouncing the scandal as the inevitable result of Apple adrift in the leadership vacuum left by its departed visionary: “This would never have happened if Steve had been there.” There’s going to be a lot of bullshit like this in the months ahead, I’m afraid.

But it is true that, at some distant point, people will look at Apple and have to decide, as well as they can, whether the company they see is truly living up to its founder’s standards, or whether it shows the first signs of an inevitable decline. Apple could easily remain unassailable with no input at all from Jobs for at least three years, and probably closer to five. By then, the tech landscape may have shifted sufficiently to allow a smaller, faster competitor to undermine Apple’s dominance or to establish a new computing paradigm ahead of it. This is going to happen eventually; it’s just a matter of when. The only real question is: will it happen sufficiently far in the future that no one can reasonably blame it on Jobs’ absence? Indeed, could Apple remain dominant for so long that Jobs himself one day becomes a hazily remembered, almost mythic figure like Henry Ford, with no direct associations with any of Apple’s then-current products?

I think it could happen. If it does, that will be the true confirmation of Steve Jobs’ genius. He would not have merely started Apple. He would not have merely rebuilt it from a teetering computer company into the world’s most valuable technology company, capable of redefining entire markets at a stroke. He would have given it a soul, and not just a soul but his soul — the one thing even some of his greatest admirers were convinced he could not do. He would have achieved a kind of immortality: a cluster of dedicated people who absorbed his ways of thinking and distilled them into an essence that can be taught and passed on after he was gone. If he succeeds in this, then there is no telling how long Apple could remain in its present dominant position. Jobs came back to Apple 15 years ago. What could Apple be in another 15 years? It could come back down to earth, become just another successful purveyor of computers, gadgets and lifestyle accessories. Or it could be something that no one today can see, an integral part of industries we haven’t yet imagined. We might even one day call it the most powerful and innovative company that has ever been — greater than U.S. Steel, greater than Ford, greater than AT&T or Microsoft — a company so ingrained in our lives that it literally has no precedent.

Knowing what little I do about Steve Jobs, I am guessing that is the legacy he strives for. Will he succeed? I wouldn’t bet against him. How amazing it is to think that for all Jobs has accomplished, today really only marks a new beginning.

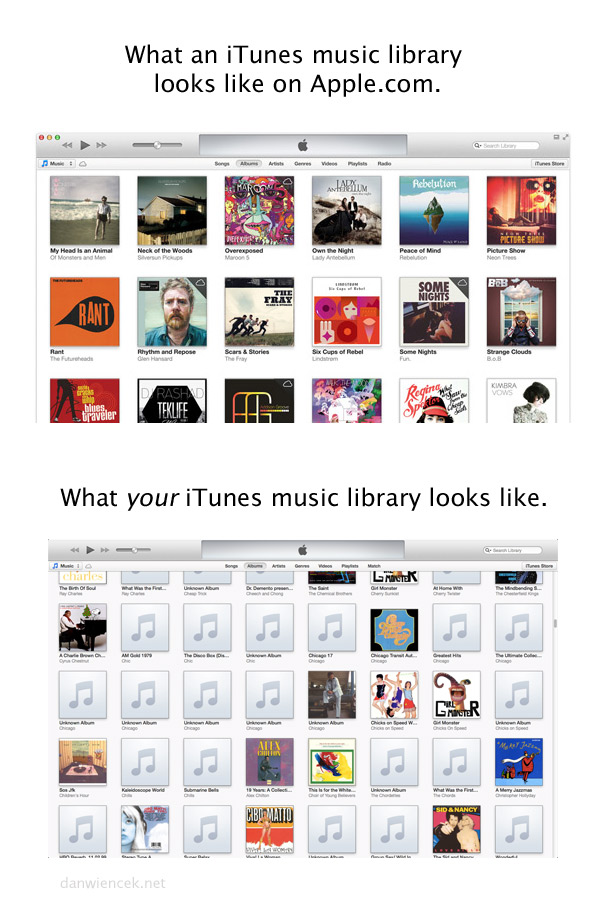

I am more-than-averagely obsessive about my iTunes library. And yet, this is what most of it looks like. Ever see those pictures of ancient relics being restored in museums, when they’ll have exactly six pieces of some ancient textile and try to somehow fill in the gaps? It’s kinda like that.

I am more-than-averagely obsessive about my iTunes library. And yet, this is what most of it looks like. Ever see those pictures of ancient relics being restored in museums, when they’ll have exactly six pieces of some ancient textile and try to somehow fill in the gaps? It’s kinda like that.