In September 1970, a famous comedian in a suit and tie went onstage at the Frontier hotel in Vegas and, before a drunk, peevish audience of golfers and conventioneers, inaugurated a revolution in stand-up comedy—and got himself fired.

“I don’t say shit,” the comedian told the crowd. “I’ll smoke a little of it, but I won’t say it.” As pivotal moments in popular entertainment go, it may not quite rank with Dylan going electric at Newport in 1965. But in a town whose comedic taste ran to the it’s-all-in-fun nouveau-minstrelsy of Sinatra and the Rat Pack, to out yourself as a foul-mouthed dope smoker was tantamount to throwing a drink in the Chairman’s face. For George Carlin, it was a shot across the mainstream’s bow. Sick of pandering to the prejudices of an intolerant white middle class, he was ready to risk his livelihood to become the first stand-up of the Woodstock generation.

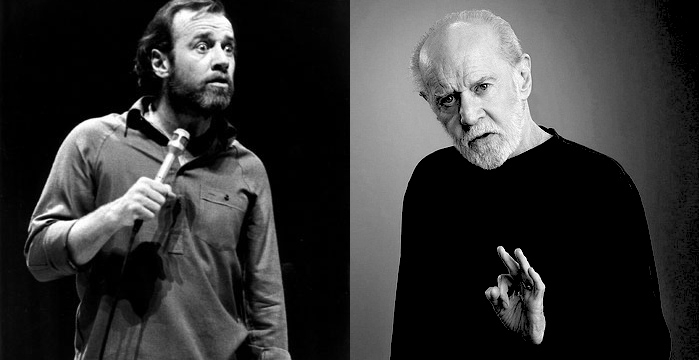

The idea would have seemed foolhardy even a few years earlier. Occasional mavericks like Lenny Bruce and Dick Gregory notwithstanding, the career of a successful comedian followed a predictable, orderly path: from radio to nightclubs to talk shows to theaters until, with luck, the ultimate reward of movies. Carlin ascended this pyramid as a mainstream comic, and, incredibly, grew a beard and did it all over again. He forced the establishment to re-accept him on his own terms, in the process expanding the very idea of what “mainstream” comedy could be. Gone were the square routines about game shows and TV commercials. In their place came openly drug-flavored ruminations about language, culture, and religion that make up the most familiar body of work of any comic of the last forty years.

Born in 1937 and raised in the then-Irish neighborhood of Morningside Heights, George Carlin had no aspirations to be a revolutionary; his chief aim was to avoid getting his ass kicked. The son of a working mother and an absent father, he honed his verbal gifts on the streets of the Bronx, where a well-timed remark might be all that saved him from a beating by the gang from up the block. Quitting high school to pursue full-time his dream of becoming the next Danny Kaye, he landed his first radio job at nineteen, and soon had worked up a comedy double act with a newsman colleague, Jack Burns. “Burns and Carlin” flirted with edgier, more socially conscious material before soon going their separate ways, but Carlin on his own was too ambitious to risk derailing a promising career. He spent the latter half of the sixties working a hard grind of talk shows, B-movies, and seedy middle-class drinking holes, increasingly aware he had nothing in common with his audiences, and that his own act was becoming an embarrassment to him.

When he finally hoisted his freak flag in 1970, he had the advantages of a well-known name and an ear for the nuances of voice and language that let him mimic everything from a hyperactive AM deejay to a first-generation Irish barfly. Beyond that was the accident of fate that found him in his mid-thirties at a time when, as he put it, “the whole country seems to be either 18 or 50.” Too young to mourn the passing of the social order the sixties had demolished, yet too practical to be swept up by the utopian optimism of the youth movement, he straddled the generation gap with unrivaled ease. He could deconstruct the absurdities of contemporary speech as easily as hit you with a killer fart joke—and in a single routine, too.

This process survives today in the six albums Carlin recorded for Little David records, which contain virtually all of the material for which he remains famous: “Baseball and Football,” “Class Clown,” “God” and, most famously, “Seven Words You Can’t Say on TV” (“shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker and tits”–all he could think of in one sitting). He invented so-called “observational comedy” with a single remark: “Anything we all do–and never talk about–is funny.” His records, like Richard Pryor’s, became valued contraband among underage listeners, prized as highly as joints or Playboys and passed from friend to friend with a ritualistic fervor Jon Stewart likens to a rite of passage.

Carlin’s invention began to flag at around the end of the seventies, and by the start of Reagan’s second term drug use and ill health had sapped most of the vitality from his act. As comics like Steve Martin and Robin Williams became the new innovators in stand-up, the public image of Carlin froze into a caricature of the aging hippie, churning out pothead wisecracks (“Know how you can tell when a moth farts? He flies in a straight line.”) for audiences as old and out of it as he was. The image was not without truth—for a time.

For in the early nineties Carlin, who had already proved American lives could have a second act, reinvented himself again, this time as a raging, misanthropic prophet of doom, whose comic distance from life had grown so vast it literally encompassed the entire cosmos. Gone were the stoner’s winsome, “D’ya ever notice—?” wonderings; in their place, a pissed-off old man who paced the stage like a penned lion, unable to hide his contempt for a frightened culture eager to trade its freedoms for the illusory comforts of euphemism and “sneakers with lights in them.” In the world of comedy, where groundbreaking talents succumb to either early death (Bruce, Sam Kinison), infirmity (Pryor), or embarrassing movie careers (Williams), such a transformation is unprecedented. Perhaps it’s not so outrageous to compare Carlin to Dylan, another artist who’s found renewed vigor among the disappointments of growing old. Both forever expanded the vocabulary of their medium, and both offer permanent warning against ever dismissing an artist as “past his prime”–though Dylan, it must be said, has yet to come up with a really good fart joke.