Summers didn’t used to be like this. As a kid in the suburbs, I would run from the coolness of our front porch into a street warmed to perfection by a sun that never seemed to overstep its bounds. Temperatures tended to hover in the low eighties most days, with the occasional bursts of rain or heat. There were breezes that actually felt refreshing, rather than like blasts from an oven.

This is not nostalgia for the past. A lot of things sucked back then. But in general, the weather wasn’t one of them.

I know this because the kind of hellishly hot days we now experience all the time in Chicago — days when the air lays on you like a searing blanket, thickening your breath, impossible to ignore — were the days I looked forward to as a kid, and there weren’t all that many of them. Hot days were swimming days. When I was young, my neighbors had a pool; later on, we had one. I was never one of those kids who could swim in any kind of weather. Eighty-two degrees is a perfect summer day, but too cool for swimming, at least for a skinny kid with a poorer-than-average ability to regulate his own body temperature. When the weatherman forecast a day in the nineties, it was a treat — it meant there was definitely going to be swimming somewhere, and on a warm day like that, there was no reason to get out of the pool, save for the occasional food and bathroom break. (There is nothing quite like the mix of pleasure and icy agony of going into an air-conditioned house wearing a wet bathing suit on a ninety-plus-degree day.)

Various children of the '80s beating the heat. I'm the kid at center left with the somewhat skeptical look on his face.

I don’t recall precisely when I noticed that this fine homeostatic balance was upset, but I’m pretty sure it was before I had a real understanding of what “global warming” meant. Seemingly all of a sudden, air conditioning went from being an occasional amenity to a vital tool for survival, running for days and even weeks on end. When I began driving, I rarely used my car’s air conditioner: better to feel the wind in my face, I thought, and besides, it’s not that hot out. Now it’s constantly that hot out, and that humid on top of it.

The only consolation we have is that the heat affects pretty much everyone to the same degree. There is a sense, at least on my part, that everyone is in the same boat, dealing with the same back sweat, the same lethargy, the same lingering sense that one should never be outdoors and among strangers while feeling this sticky, smelly and gross. Even with air conditioning, the heat cannot be managed away. It is nature intruding on us coarsely, insisting we give it its due. It’s a little humbling, when all is said and done, and in some lobe of my brain capable of abstract reasoning, I think that’s a good thing. But I still hate the goddamn heat.

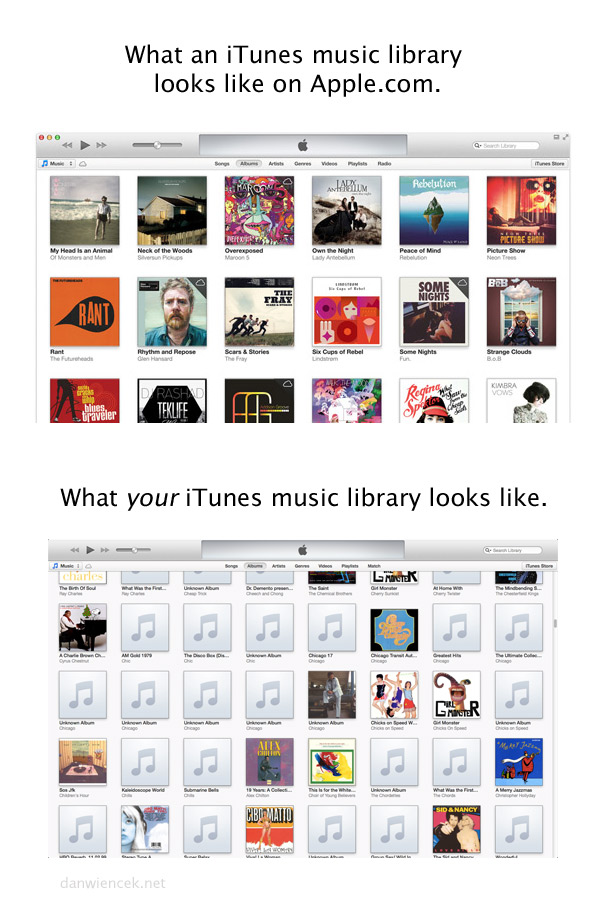

I am more-than-averagely obsessive about my iTunes library. And yet, this is what most of it looks like. Ever see those pictures of ancient relics being restored in museums, when they’ll have exactly six pieces of some ancient textile and try to somehow fill in the gaps? It’s kinda like that.

I am more-than-averagely obsessive about my iTunes library. And yet, this is what most of it looks like. Ever see those pictures of ancient relics being restored in museums, when they’ll have exactly six pieces of some ancient textile and try to somehow fill in the gaps? It’s kinda like that.