My brother-in-law sent me this via text message. It’s good to see a church not holding a grudge from the whole “bigger than Jesus” thing. (Here’s a link to the church in question.)

Posts Tagged → Beatles

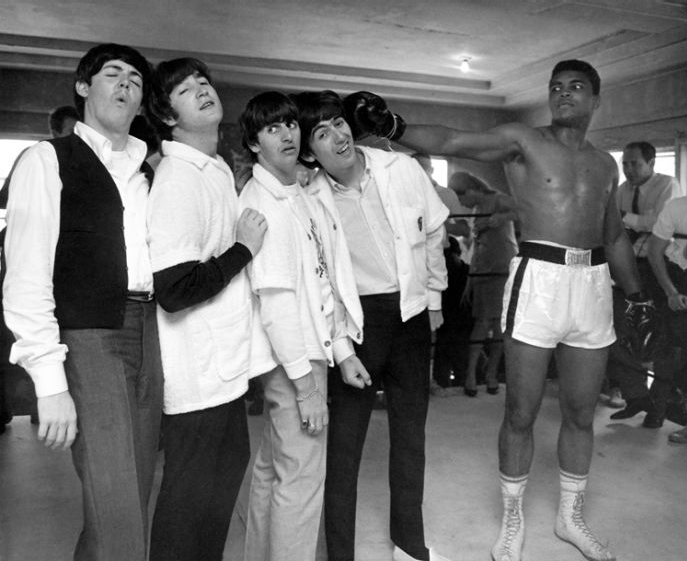

The Beatles Meet Cassius Clay, February 1964

There is a tumblr called awesome people hanging out together. It lives up to its name. There are classic photos everyone knows, and quite a few I had no inkling of. It’s cool to see Jimi Hendrix greeting Janis Joplin (I can’t link to the photo itself) backstage — for all I know it’s the first time they ever met. Maybe the only time. Or Michael Jackson pretending to punch Mr. T — as apropos a summary of the early 80s in a single image as you can probably imagine.

One thing I was expecting to find, and did, was this:

There are lots of pictures of the Beatles clowning around with Cassius Clay, as he was still known then, and this one and the variations of it are the best known. It might not occur to you on seeing it that the Beatles and Clay had no idea who each other were. The photo opp was arranged by their respective handlers, who had some inkling of what it might mean to bring these two phenomena together: the British invaders who were taking over American popular music, and the African-American dynamo who, not content to redefine the sport of boxing, went on to create the template for mass-media sports celebrity — he had already started doing it when this shot was taken.

We see this photo now and marvel that it happened, that these five people ever occupied the same space together. It’s like an improbably real version of those cheesy prints that show Bogart, James Dean and Marilyn Monroe hanging out in the same pool hall. The Beatles and Muhammad Ali, to give him his proper name, are titans, figures who stand outside of popular history. It looked a little different to viewers back then. The Beatles were a teenybopper fad in February 1964, when they went to visit Clay as he trained for his first title fight. No one, perhaps not even the Beatles themselves, realized how pivotal their presence would be as the 60s took their strange, epochal course. And Clay was something of a nine-day-wonder himself, a braggart expected to have his clock cleaned by Sonny Liston. Probably a lot of people simply wanted it to happen, wanted to see the loudmouth get his comeuppance, just as a lot of people waited, and waited, for the Beatles to fall on their faces and prove how shallow and fleeting their presence in the culture really was.

But the Beatles went on to prove that rock music could expand beyond anyone’s preconceptions, taking politics, manners and culture along with it. And Ali proved not only that he was a great fighter — indeed, that he was as great as he said he was, which hardly seemed possible — but that a sports figure could be just as culturally radical, just as transformational, as any artist, politician, philosopher or pop musician.

It hadn’t happened yet. No one was seeing it coming. This is a photo of the moment before everything changed.

Merry Christmas, Music Biz. Love, the Beatles.

If you’re the type who would care, you probably know: the long-promised remastered versions of the Beatles’ albums will finally be released this year on September 9. (“Number 9” … yes, we get it. Even better if they had come out in October — i.e., the one after 9/09.)

I’ve been following this story — what very little there has been of it to follow — for about three years now, ever since the Apple Computer/Apple Corps trial, when the secretive Neil Aspinall was forced to admit in court proceedings that he was, in fact, supervising a total revamping of the group’s catalog. Questions that had been fruitlessly batted back and forth are now finally answered. Yes, the mono Sgt. Pepper will come out; in fact, all of the albums will be available in mono (except for Abbey Road, which was never released that way). Yes, the music has been cleaned up in a way that, we are assured, adds the punch expected of contemporary rock while still being true to the original mixes’ ambience. Yes, even the original, oddball stereo mixes of Help! and Rubber Soul will come out, which most people will likely not bother to listen to more than once. And while no details of packaging have been released, we know we can get all these goodies in two fell swoops: all of the stereo albums and all the mono albums will be available in two separate box sets.

It was that last detail that really brought it home to me, that illuminated what should have been a patently obvious fact: they are going to sell a shitload of discs. Continue reading

Gear Fab

I once told a colleague that EMI could release a straight dump of the Beatles’ master tapes — every inch of chatter, false starts, tuning, George getting pissy at Paul — and I would buy it. EMI hasn’t given me that opportunity, so I make do with what’s available. Which is why this book is having me salivating.

On coolness and Beatles

I recently resurrected an old piece I wrote for Pop-Culture-Corn called “How Cool Is Paul McCartney?”. The original feature, now lost somewhere deep in the belly of a Google backup drive, found four writers each making the case for a particular Beatle as the apogee of Cool. I was asked to represent McCartney because of my avowed fondness for his work; I accepted because I was, and still am, sick of the sneering attacks music critics have been aiming at him since roughly five minutes after John Lennon’s death.

And also, truth be told, because I have an unfailing sympathy for the uncool. And McCartney, no matter how cool his various achievements, will always, personally, be uncool. As many a sardonic wag has remarked, The Beatles are dying in order of coolness. Ringo’s next.

Reading my essay over now, there are a few things I would change: I’d tone down the Yoko bashing, for one thing. (The creepy, unhealthy psychodrama of the Lennon/Ono marriage rests more with the groom than the bride.) For another, I actually think I could’ve made my case stronger. Forget for a moment the fact that, in 1966, McCartney was among the handsomest, most interesting and most sought-after (read: cool) figure in arguably the most culturally significant city in the world at that moment. He went where he wanted, slept with whom he wanted, did whatever the fuck he pleased; no one would turn down a chance to trade places with Paul McCartney. But forget all that and just stick to what you can quantify. McCartney was the first of the Beatles to write his own songs, the first member of the fledgling Quarrymen who actually knew how to play. (Lennon played the guitar with banjo chords until “Paul taught [him] to play properly.”) Unlike Lennon, who before meeting Ono deeply mistrusted anything avante garde, McCartney eagerly absorbed the musique concrete of Stockhausen or Glass, and was the first of the Beatles to rip the eraserhead out of his tape recorder and begin making tape loops in his home studio. Without McCartney, “Tomorrow Never Knows” would have consisted of John Lennon banging out C on his acoustic guitar, and the world might have been spared “Revolution #9” altogether. It was McCartney who pushed the Abbey Road engineers to overdrive the trebly guitars of “Nowhere Man” and who had the idea of recording his bass through another amplifier instead of a conventional microphone. Critical opinion has swung between either Sgt. Pepper or Revolver as the Beatles’ masterpiece — and both are dominated by Paul, from behind the desk if not always behind the mike. This is something beyond cool; there are maybe a dozen people in 20th century popular music who can claim achievements of this rank.

And yet.

I will defend McCartney’s creativity and experimentalism to the end. Yet my heart-of-hearts favorite Beatle?

John.

John Lennon was a deeply wounded man, a man for whom braggadoccio and cruelty served as a mask for an insecure boy who never stopped resenting all the grownups who thought he was worthless — and who he must have at least occasionally suspected were right. Lennon’s earliest efforts at “honest” songwriting were exercises in formulaic self-pity, no more or less fundamentally honest than the likes of “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” But somewhere around 1965, Lennon figured out how to tap his inner conflicts without resorting to sad-clown poses. He presented the tangle of his psyche with all its contradictions intact, grounding his songs in uncertainty, hesitancy, confusion. Lennon’s finest songs — “She Said She Said,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “I Am the Walrus” — are snapshots of a tumbling psyche in mid-churn.

The usual critical line is that McCartney, by contrast, was shallow, preferring to pander with a smiling face and a thumb perenially turned upward. That’s an oversimplification. McCartney aired his share of emotional dirty laundry, most famously in “We Can Work It Out,” positively Lennonian even before his partner added its rather impatient middle eight. But McCartney, ever the forward-thinking optimist, tended to present his emotional dilemmas post-facto, their tensions already resolved. If Lennon’s songs were the work of a skeptic, McCartney’s were the product of a believer. Think of “Let It Be” and its famous opening lines:

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me

No sooner is the crisis introduced than the solution arrives. Lennon could have handily written an entire song about finding himself in times of trouble — indeed I seem to recall a song called “Help” written in 1965 or so — but for McCartney, it is merely the precursor for the dramatic uplift, the consolation that is the song’s true message. “Hey Jude” of course is an anthem of consolation, a plea for optimism that is both cannily calculated and wholly heartfelt. Both “Hey Jude” and “Let It Be” are gorgeous songs, and the former is among the Beatles’ very finest, but unlike Lennon’s finest, they begin after the crisis has taken place, not in the middle of it.

So I will always admire Paul’s amazing abilities, his drive, and his belief that the ordinary and the positive are worth celebrating. But it’s John who, briefly and wonderfully, speaks to me.

How Cool Is Paul McCartney?

It was a moment of pop-culture surrealism worthy of The Simpsons: Paul McCartney, schmoozing backstage at the MTV awards, innocently picks up a baguette and bites into it. His front tooth suddenly shoots out of his mouth, and while it doesn’t land into anyone’s Ketel One–and-cranberry, those looking on are flabbergasted enough. Yes, the gap-toothed McCartney confesses: the Cute Beatle wears a fake tooth. The reason? A motorbike accident more than thirty years ago, in which a stoned McCartney flipped over his handlebars and fell face-first into a dirt path. Though the accident had been public knowledge at the time, McCartney kept the full extent of his injuries hidden for more than three decades, the best-kept secret in all of Beatledom.

Somehow it tells you so much about Paul McCartney: the need to present a sunny, all’s-well face to the world; the juvenile streak that manifests so often in his music (even John knew to stay away from dangerous machinery when he was stoned); and most importantly, the essential mystery that has been hiding in the public’s plain sight ever since the Beatles first came to the consciousness of a generation. McCartney was the smiling, puppy-eyed charmer, and he adopted that characterization so expertly that few people to this day have bothered to look past it. They see a shallow media persona and assume it hides a shallow man, and they’re wrong.

It was not always so. Anyone involved in London’s artistic and cultural ferment of the mid-sixties (which John Lennon largely wasn’t, preferring to shuttle his friends out to Weybridge rather than mix it up at nightclubs) knew McCartney as a key figure, popular among the cognoscenti for his intelligence, curiosity, and openness to new ideas. Naturally his cultural pursuits weren’t allowed to infringe on his favored pastimes of getting high and sleeping with women, yet he still found time to help launch London’s first countercultural newspaper and bookstore, talk movies with Michaelangelo Antonioni, collect the work of surrealist painter Rene Magritte years before anyone else thought it worthwhile, be seen with one of London’s most beautiful and talented actresses, and — oh yeah. And write all those songs.

The greatness of McCartney’s songwriting is so self-evident as to be beyond dispute. It need only be pointed out that his work is far less simplistic than is often claimed. “When I’m Sixty-Four” may be a light-hearted toe-tapper, but the fear of aging lying beneath its charming façade can ambush an unwary listener (“indicate precisely what you mean to say/Your’s sincerely, ‘Wasting Away'”). “You Never Give Me Your Money” is a heartbreaking confession of the Beatles’ decaying carmaraderie, simultaneously recriminatory and celebratory; I’ll take its stunningly versatile four minutes over Lennon’s chest-thumpingly obvious “God” any day, thank you. And “Penny Lane,” arguably his finest single achievement, is a joyful, smutty, kaleidoscopic remembrance of childhood every bit as mind-blowing as its more lauded companion piece, Lennon’s “Strawberry Fields.” (Spend a half-hour sometime pondering the nurse who “feels as if she’s in a play” but “is anyway.” Your head may explode.)

So how, despite his undeniable achievements, has McCartney acquired his reputation as a lightweight, middlebrow balladeer, cuddly and unthreatening? Truth be told, the fault is mostly his, and goes beyond the admittedly depressing decline in the quality of his work around the mid- to late seventies. The birth of Safe Paul McCartney can be traced to the summer of 1967, when Rebellious, Intellectual Paul McCartney admitted to a BBC reporter that he had not only taken LSD (the first pop star to make such an admission), but found the experience beneficial, even a little fun. The establishment came down swiftly and mercilessly, deriding him as an “irresponsible idiot” and generally making life difficult for every drug-taking pop star from then on. While John Lennon never lost his taste for outrageous remarks, McCartney has made nary an offensive peep since, and by the mid-eighties was confessing in interviews that his own family was “a lot like” that depicted on The Cosby Show. Thus the perception of Paul McCartney as an ordinary family man, a perception that has preserved his privacy while chopping away at his artistic reputation.

Happily, there are signs that McCartney is finally coming out of the woods and achieving parity with his martyred ex-partner. A pair of studio albums reminded the public of both his songwriting prowess (Flaming Pie) and his rock n’ roll pedigree (Run Devil Run); a new biography called Many Years From Now finally gave him due credit for his role in advancing the Beatles’ art; and the tragic death of his wife Linda, as sincere and humble a celebrity’s wife as any you’d hope to meet, reminded the media that a life of simple decency was nothing to sneer at. Of course there will always be naysayers; Yoko Ono, appalled at what she regarded as a slur on her late husband’s memory, shriekingly attacked Many Years From Now as a compendium of lies, claiming McCartney was merely “Saglieri to John’s Mozart” and that McCartney made little contribution to the Beatles other than insuring they all turned up on time. Her remarks, in their utter falsity and paranoia, make her pitiable. Lennon at his angriest never claimed to be the sole genius behind the Beatles. And when, years later in America, he would weep listening to “My Love” or gently croon “Here There and Everywhere” to Yoko from their white grand piano, he demonstrated something that his widow is still too blinded by jealousy to appreciate: that a song that insinuates itself into your heart is never simple, and never easy. The seeming effortlessness comes from genius, know-how, hard work, and an emotional generosity that’s impossible to feign. May we all live to see them receive the respect they deserve.

Originally published on Pop-Culture-Corn around ’99 or so.