I forgot to post this earlier in the year, but the April 2017 issue of The Blotter featured two of my poems, “Demonstration” and “Walking the Path.” The online version can be read at this link; you can find my work on pages 12-13.

Author Archives →

Removing Statues and Planting Trees: Charlottesville and Beyond

This is not an essay denouncing the violence in Charlottesville, or our president’s disgraceful response to it. Those things are self-evident and, to the extent they’re not, others have spoken about them with more eloquence and insight than I could. I want to talk instead about why Charlottesville happened, why it’s likely to happen again and how we might come through this struggle in a better place than where we began.

First, a little background.

This country has never truly reckoned with the consequences of the Civil War and its aftermath—especially, I think, the aftermath, the true, horrid scale of which I believe still remains largely unknown by white Americans; it certainly was to me for most of my life. Jim Crow was more than just laws that kept black people away from the ballot box, a disgraceful enough thing in itself. It was a collusion of culture, politics and the legal system to recreate slavery in all but name, exploiting blacks for their labor while depriving them of everything they were entitled to as newly recognized American citizens. This was done not only through “literacy tests,” grandfather clauses and whites-only drinking fountains but through the convict lease system, consciously racist zoning laws, and of course, vigilante terror and murder, to name just the most obvious things.

The Robert E. Lee statue that was the ostensible cause of all this is a relic of this system. Most of the Civil War statuary dotting courthouses and public squares in Southern towns was not made during the war or in its immediate wake. These figures were erected from the 1900s through the 1920s as totems of Jim Crow, meant to remind both blacks and whites of the level each group occupied (low and high, respectively) on the social pyramid. They are subtle instruments of terror wrought in bronze.

As these monuments began to spring up, there came with them what we now know as the myth of the Lost Cause, the revisionist belief that the Civil War was brought about not by slaveholders determined to protect their human property, but by an overzealous, self-righteous and hypocritical Northern government bent on overrunning the states’ rights guaranteed in the Constitution in order to clear the path for a smothering, all-encompassing Federal authority. The Confederate States of America, a would-be oligarchy founded on racial and religious bigotry and with the explicit goal of expanding slavery throughout the Americas, was recast as a noble-but-doomed final stand in the defense of a now-vanished American ideal.

This historical lie, aided and abetted by whites in the North as much as the South, is why the Stars and Bars remain for many Americans (who often do not consider themselves racist to the slightest degree) a symbol of proud American defiance and self-determination, rather than an emblem of hatred on par with the Nazi swastika. It explains why people wearing the insignia of a defeated insurrectionist movement that sought to leave the Union outright now regard themselves, without irony, as the true patriots and lovers of America. By extension, statues of Lee, Forrest, Longstreet et al, gilded in the patina of the Lost Cause, serve a similar purpose in valorizing this deracinated Confederacy. Civil War statues and the Confederate battle flag are not racist, we are told—they’re our heritage, and no one should be made to feel ashamed of his heritage.

To be sure, the Klan-saluting, torch-wielding crowds protesting in Charlottesville seemed very much motivated by racism, however much they speciously invoked their “heritage.” But these monuments haven’t endured this long solely because of the small minority of Americans who think and act like the demonstrators at Charlottesville. They endure because as a nation we have failed to honestly confront what they stand for—because after all this time, we refuse to agree on what the Civil War meant, or engage with what its post-Reconstruction aftermath set out to achieve.

Until now.

Remember that what prompted this whole appalling display was the Robert E. Lee statue in question was set to be removed from its privileged place, because the leaders of Charlottesville could no longer countenance the insidious ideals that had led to its creation. The neo-Confederates protesting this were lashing out in fear, and their fear is fully justified. The lie upon which they have constructed their pride and sense of worth is being challenged, not just by far-off liberal interlopers but by their own friends and neighbors. People both in the South and beyond it are seeing the myth of the Lost Cause as just that—a fable designed to protect the privileged by obscuring the brutality on which that privilege was founded.

After more than 100 years, the cracks are indisputably beginning to show. New Orleans removed a statue of Lee from public view a few months ago. The Republican governor of Maryland just announced his intention to remove a statue of the Supreme Court justice who wrote the Dred Scott decision. The mayor of Lexington, Kentucky announced—ahead of schedule, spurred on by the violence in Charlottesville—that he intended to have two Confederate statues relocated from the former city courthouse, now a visitor’s center. More cities and states are sure to follow.

Expect more outbreaks like Charlottesville as the weight of public opinion turns slowly, inexorably against these background furnishings of Jim Crow. It will undoubtedly get worse before it gets better, and it’s perfectly appropriate to be outraged and sickened at these spasms of racist violence, and at the president who responds to them with cowardly equivocation. But the fact remains that this conversation has been long overdue, and having it was never going to be easy. Do you remember when well-meaning politicians used to talk wistfully about the nation “having a dialogue” about race in America? This is what that looks like.

There is a saying among the Chinese: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.” It is tempting—and futile—to wonder what might have been had Reconstruction continued as Lincoln had envisioned it, and Jim Crow and the Lost Cause had shriveled and died before ever having the chance to bloom. But it is not 120 years ago or 20 years ago, and today we are tasked with planting trees in some very hard, stubborn earth. The work will be long and brutal and not all of us may live to see it bear fruit. Yet when it is done—when those seeds have finally taken root and resisted all efforts to pull them free—we can look back at our efforts and our sacrifices and know that they were given in pursuit of a worthy goal, one which, once achieved, will leave our nation better than it was before.

Originally published on Medium.

New Poem, Quick Update [Updated]

As promised in the previous post, a new poem is out. Read “Weighing the Stars” online at Milk Journal.

Update, November 2017: Milk Journal seems to be kaput. Rather than allow the poem to disappear into the memory hole, I am reproducing it here. Pardon the .jpg; advanced online typography is not really my forte.

Roses Are Red, Violets Are Blue: It’s Time for Poet’s Corner

Hello dear readers, you few, you happy few, you.

The site has been moribund for a few reasons, not least of which is it just wasn’t working. I don’t know how it first happened nor how, after some random clicking behind the scenes, it suddenly righted itself. However it came about, all posts on this blog are now accessible again, which makes updating it seem tangentially more worthwhile.

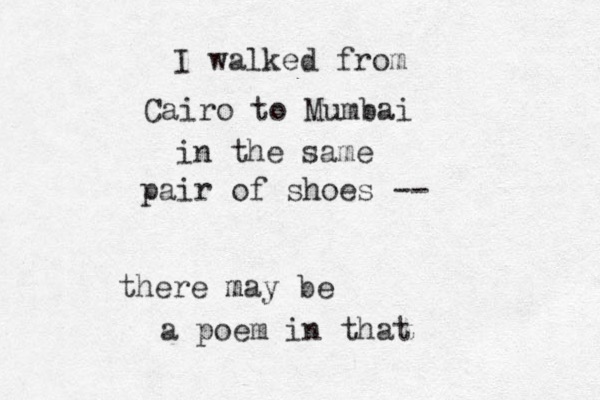

Early this year, while trying to write a YA novel that seemed to refuse every opportunity to be written, I found myself revisiting some old poems stashed in an obscure corner of my hard drive. I thought they weren’t so bad, and that it might be fun to write a few more. Fast-forward to roughly now, I have been firmly bitten by the poetry bug and so the energy that might have gone into pithy blog posts has mostly gone in that direction.

Will I be publishing poems here? Probably not. I’d rather let a journal (with, you know, an actual audience) have first shot at anything I produce. And speaking along those lines, my first accepted piece can be reviewed online in the e-zine Crack the Spine. My poem “The Air of the Room” can be read for free in Issue 195.

In addition, Hypertrophic Literary published two pieces, “I Love This Woman” and “New Red,” in their Fall 2016 issue. You’ll need to shell out for this. Totally worth it though.

And there we are. I have a couple more pieces forthcoming but I’ll post more about that when I have something to link to.

Story in Three Sentences

They met over artisan whiskeys in a bar that had once been a dentist’s office. With little to go on, she thought he could be kind to her, safe enough in his own skin to teach her to live safely in hers. It broke apart years later, amid tears and pleas and a final, raging silence, on the floor of a hollow space that had once been a whiskey bar.

Inspired by this challenge.

Police State

I was born in 1971, too late to have witnessed the convulsive events that characterized the end of the 1960s. I know of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago from reading about it and seeing old news footage. The massacre at Kent State I knew chiefly through the song Neil Young wrote about it. I always wondered what it must have been like to live through that, to see our country turning on itself like a snake swallowing its own tail, and ask, “What’s happening to us?”.

I’ve been following the story of Ferguson, Missouri, and the riots and unrest that have followed in the wake of the death of Michael Brown. And I think, maybe, I get it now.

The pictures that have emerged from Ferguson are the most shameful images I have seen of American life since our first glimpses of the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans, after Hurricane Katrina drowned it. If you can look at images of a garishly militarized police force training assault weapons on unarmed American civilians, and not feel some mixture of horror, outrage and despair, I really don’t know what to make of you. This is exactly the kind of thing that, we used to tell ourselves — accurately, for the most part — only happened in other countries.

It’s true that there has been rioting in Ferguson, and at least a possibility that police officers were threatened by people in the crowd. And none of that — neither threats nor rioting nor anything else — justifies the grotesque display of paramilitary zeal that ensued. A police force that properly remembered its mission to serve its community would have gone into this situation with the goal of defusing it, of letting tensions bleed off and subside. The Ferguson police seem to have made the opposite decision: to meet force with force.

Here is what Jelani Cobb wrote in the New Yorker:

What transpired in the streets appeared to be a kind of municipal version of shock and awe; the first wave of flash grenades and tear gas had played as a prelude to the appearance of an unusually large armored vehicle, carrying a military-style rifle mounted on a tripod. The message of all of this was something beyond the mere maintenance of law and order: it’s difficult to imagine how armored officers with what looked like a mobile military sniper’s nest could quell the anxieties of a community outraged by allegations regarding the excessive use of force. It revealed itself as a raw matter of public intimidation.

It’s important to bear in mind that there is another, equally important objection to the conduct of the Ferguson police. Beyond being grossly excessive, it was incompetent. They could hardly have made the situation worse if they tried. It’s staggering to think that no one in a position of authority in that town thought to wonder, given a populace severely on edge from what they considered an unjust use of police force, whether suiting up the police in riot gear and sending them into the streets in military-surplus armored vehicles with roof-mounted machine guns might be, you know, misconstrued. As Matthew Yglesias wrote, “you do crowd control with horses, batons, and shields, not rifles. You point guns at dangerous, violent criminals, not people out for a march.” The law-abiding people of Ferguson were done a terrible disservice by the people sworn to protect and serve them. And you needn’t take my word for it, as a cursory glance at the Storify page Veterans on Ferguson reveals. A few of the more on-point comments:

In the USAF, we did crowd control and riot training every year. Lesson 1: Your mere presence has the potential to escalate the situation.

Also, we contained riots in Baghdad next to mosques with less violence than the police are employing.

A lot of vets, me included, would go to Ferguson and gladly teach some classes on crowd control and patrolling[.] You are fucking it up.

I do not write this from any kind of anti-police animus. I’ve relied on help from the police several times in my life and was grateful each time; civil society could not function without them. By the same token, I do not recognize the generous, selfless police officers I’ve encountered in these images from Ferguson, and I’m confident that were I a police officer myself, I’d be every bit as appalled by what has occurred.

As of this writing, it appears cooler heads are starting to prevail. The Missouri State Police have taken charge of the situation, and its captain has taken the radical step of opening a dialogue with Ferguson citizens to begin to undo the damage of the last four days. I am relieved. Maybe Ferguson will escape its name being inscribed alongside Kent State and Chicago on the list of the grossest abuses of state power in America. And maybe, as the dust settles and we begin to take stock of what’s happened, we can have a long-overdue conversation on the wisdom of arming local police forces like platoons of Marines. And, of course, there is the matter of Michael Brown: how he died, why he died, and what could have been done to prevent it.

So many conversations to have. Just so long as we do have them, that all this might not be for naught.