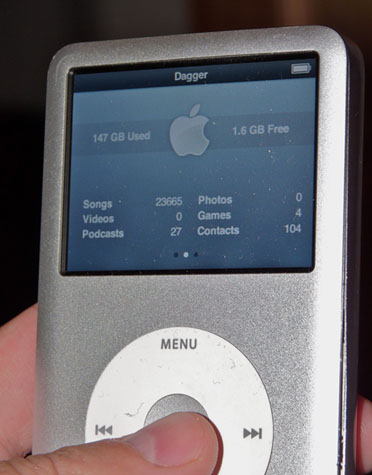

Recently my 160 GB iPod classic began showing signs of advanced age. I would fully charge it, play it a bit, leave it to the side for a day and return to find the battery nearly depleted, sometimes so low it wouldn’t turn on. I began to think it was time, that this device had finally reached the point where it could be allowed to retire gracefully.

I bought this iPod, my third, shortly after the “classic†designation was first introduced. I was thrilled: this was the first iPod large enough to hold the entirety of my music collection, freeing me from the burden of curating playlists and trying to second-guess what my tastes would be on a given day. (I have largely re-assumed this burden with my 32 GB iPhone, but that is another matter.) It did not trouble me at the time that, merely by calling its former flagship product a “classic,†Apple was signaling that the iPod’s glory days as a music device were behind it. A classic is something beyond the need for evolution or change, something that provides the same pleasures over and over, something — if I may get momentarily pretentious — more associated with memories than hopes.

So, back to my ailing iPod classic. I had some extra money and, what’s more, an impeccable justification for replacing my current model. Except I dragged my feet. I looked at the refurbished models on the Apple website and noted with approval that I could save quite a bit of money buying used. Gradually it dawned on me that I didn’t want to buy a new iPod. Not because of sentimental attachment to the current one — though I love Apple technology, the devices themselves are completely fungible to me, and I have no hesitation in dumping my current object of affection for something new and improved. The problem is that the current iPod classic really isn’t improved from the model I bought in 2008. Today’s classic supports Genius playlists and … I’m not really sure what else. There is certainly no difference of any substance. I can’t think of another Apple product so little improved over so long a time. But then, why improve a “classicâ€?

I see the logic. Apple is about iOS devices: the iPad, the iPhone and its bastard offspring, the iPod touch. The iOS platform is Apple’s chance to directly influence the evolution of an entire new computing paradigm, in a way they didn’t quite do with the Macintosh. They’d be crazy not to put all of their eggs in that basket. And let’s face it: mp3 players are so five years ago. Continue reading